MONDAY, 25 JULY 2022

The Philosopher Volume CX No. 2 Autumn 2022

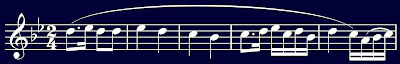

— in five movements

by Thomas Scarborough

To rephrase the marketing slogan for Heineken beer in the 1970s, metaphysics refreshes the parts that other books in philosophy cannot reach.

It was Aritsotle who started it off, around 300 BC—rather prosaically coining the term ‘metaphysics’. His intention was simply to distinguish between ‘physics’ or empirical science, and broader underlying questions that not only cannot be addressed with the same methods, but cannot, perhaps, be addressed at all.

Today, due to our greater emphasis on ‘physics’, and a profusion of seemingly incompatible knowledge and thought, books on metaphysics have tended to be few and far between. Nonetheless, the hunger for a unified account of reality has never waned, and in recent years there have been at least four introductions by professors on the subject:

• Metaphysics: A Very Short Introduction, by Stephen Mumford;

• Metaphysics: An Introduction to Contemporary Debates and Their History, by Anna Marmodoro and Erasmus Mayr;

• What is Metaphysics? by John Heil.

• And a singular book called Neues System der philosophischen Wissenschaften im Grundriss (Ground Plan for a New System of the Philosophical Sciences) by Dirk Hartmann, presented in several volumes, at an awe-inspiring price.

All of these authors seem to take a grand view of their work, as not only sweeping surveys of life, the universe, and everything, but also ‘answers’ to key questions about them. Yet assuredly, if they have produced works of such historic import, few have realised it, and thus the goal of a new, defining work on metaphysics has remained very much open over the years.

It is thus with this challenge in mind, that Thomas Scarborough, deputy editor of this site, has now produced his own 380-page volume titled simply Everything, Briefly: A Postmodern Philosophy.

Introduction

A postmodern metaphysics might seem a contradiction in terms. Metaphysics represents a unified whole, after all, while postmodernism does not. Yet one has to begin somewhere. Even the ascent of Kilimanjaro begins in the marketplace of Marangu. I begin, therefore, with familar philosophical categories—then pass beyond them.

I introduce my work in the old-fashioned way, by means of two core concepts: things and relations. There are many terms for the same, and in many cases, nuances and conflicts of meaning. One finds parallels, too, in (among other things) objects and arrangements, variables and operators, nouns and verbs.

I proceed in five movements—a ‘movement’ being a self-sufficient part of a larger whole:

First Movement: Things, relations, and meta-features

The examination of things and relations is, in the first place, vital to ethics. Ethics is a major aspect of our lives—in fact every moment of every day. There is little we do without involving some value judgement. Yet in spite of this, ethics presents metaphysics with a serious problem.

The philosopher David Hume described the problem in terms of things and relations. He wrote in his Enquiry, ‘The distinction of vice and virtue is not founded merely on the relations of objects.’ That is to say, we do not, merely by observing relations between objects, discover any moral obligation—let alone ‘some new relation’ in that connection.

On the surface of it, this problem has no solution. The alternatives, too, seem quite unsatisfactory. At the extremes, we find intuitionism on the one hand, and theological voluntarism on the other—which are, to put it too simply, a moral sixth sense, or the belief that one’s actions are a matter of divine will.

Neither of these options, or any admixture of them, offers a rational basis for ethics.

Suppose, however, that there were another way to think about things and relations. Rather than pondering how we might arrange things in this way or that, we may, as it were, zoom out instead, to view the entire expanse of things and relations from a height, and see whether we find any meta-features there.

When we begin with things and relations as a whole—as a totality—we discover that they reveal certain emergent features—or meta-features. With this, various ethical principles emerge:

• When we cast our eye over an endless expanse of things and relations, this differs fundamentally from other ways of looking at the world—in particular, bounded or self-interested views of the world which are limited in scope, or views restricted by (among other things) ethnic, religious, ideological, economic, or scientific interests.

• When we see that we are surrounded by an endless expanse of (I abbreviate) relations, we come to understand that, while the totality of relations is endless, we ourselves are finite. There is a mismatch—between the number of relations in this world, and the number we can contain in our minds. Therefore, a sound ethics will be keenly aware of the danger of our limitations.

• As we survey an endless expanse of relations, we find no reason, as it were, to plant our flag in one place rather than another. An endless expanse of relations is unable to provide us with a stable centre. Therefore we prefer an ethics of equality, rejecting domineering schemes of various kinds.

As it affects our ethics, we need a bird’s eye view, before we bring things into relation in any helpful way. This happens when we study the totality of relations, rather than any section or reduction of them.

Second Movement: Things and relations in closed systems

Any arrangement of things and relations, which is smaller in size than the totality of things and relations, represents a system. We find (for example) mathematical, scientific, ethical, theological, and philosophical systems.

We create systems wherever we relate things to things in a well considered way—more exactly, where we find a group of inter-related things which act according to a set of rules. In terms of this definition, systems may be exceedingly complex—for example, ecosystems—or, most simply, described by a single formula.

An obvious feature of systems, which we habitually overlook, is that these exclude all that they do not include. This is not a mere tautology. A system snips away anything and everything that is not thought to be vital to the system. In fact, this has to be the case, or systems would become unwieldy.

Suppose that we have a system which is so simple that we may describe it by the rule A + B = C. In order to arrive at this rule, we exclude everything not-A, not-B, and not-C. These ‘nots’ are not relevant to the system. At least, not that we suppose.

Consider the production of rubber (which equips more than a thousand million vehicles on the road). We typically use isoprene in this process, for which we often react isobutene with formaldehyde. We can over-simplify this as isobutene + formaldehyde = isoprene, or simply A + B = C.

Now isoprene enters the atmosphere, where it combines with oxygen, to create hydrotrioxide. This is an extremely reactive chemical, of which about 10 million metric tons form in the air each year—the problem of which was only fully realised in 2022.

Thus a closed system—the manufacture of isoprene—existed within an open or global system, which is the world. Yet the process did not account for its effects on the global system.

A + B = C may be deceptive, too, because it is, on the surface of it, an all-encompassing, or holistic equation. C contains everything that this equation is. If the equation itself could speak, it would tell us that it knows of nothing outside itself. But there is a world beyond it.

Now consider that, as we apply our scientific knowledge rigorously, unflinchingly, in every city and nation across the globe—‘screening things out’ being the sine qua non of the scientific method—a vast amount is ignored. In fact, taking our use of learning algorithms into account, it is unthinkably large.

No surprise, then, to discover that we left out the environment, or society, or (increasingly) contingencies of various kinds. It all has to do with things and relations which are smaller in size than the totality of things and relations. Arguably, this is the biggest problem of our time.

Third Movement: The nature of things and relations

No matter what the things and relations which we arrange—whether these be (among other things) objects mathematical, scientific, or natural—we are always doing fundamentally, essentially, the same.

This is a major statement. No matter what kind of object, entity, item, or thing (and so on) which we arrange, all arrangements of things in this world must represent fact, or they must represent value, but not both-and, as we have it today.

The fact‒value distinction has created a vast separation of science and mind. The most obvious example is the separation of the natural from the human sciences. We further separate school classes, TV programming, cabinet portfolios, even shops in malls, all across the world. All around us, we see monuments to this great divide.

For centuries, many philosophers have felt that this separation ought not to exist. There have been strenuous efforts to set it aside—and yet it lives on.

Yet all things and relations share certain vital features, and this points to their common nature. I briefly survey three of these features, without entering into them in any depth:

• Whether we are dealing with fact or with value, both are arrangements of things. Either things ‘are’ arranged like this, or they ‘ought’ to be. In terms of my metaphysics, it is only ‘ought’. This applies even to the arrangement of things in the hard sciences. Today, science is no longer thought of as an ideal, ‘is’-ordering of our world.

• We set bounds to every arrangement of things—subjectively, we should add. Even in science, wrote the philosopher of science Stephen Toulmin, ‘Scientific law shows on it nothing as to its scope.’ We choose what is not-C. Cambridge philosopher Simon Blackburn wrote that we select particular facts as the essential ones.

• All things are abstractions. Whether we speak the language of (for example) mathematics, science, or ordinary language, all the things we arrange are ‘strip-downs’ of reality, on a continuum of abstraction. For this reason, too, they do not represent a complete or perfect fit—an objective fit—with reality.

We need to leave this subject too soon. Most basically, all things are related to all things, as we think they ought to be. All arrangements of things have this common nature of ‘ought’.

How should this matter to us?

Most obviously, it is crucial to the creation of an integrated metaphysics that we are not left with two kinds of reality: fact and value. That carves up what we feel should be a unified world of thought—sundering fact from feeling, quantity from quality, systems from narratives, and so much more.

Further, if everything is marked by subjectivity, as is the claim here, it is dangerous to imagine that it is objective: objective history, objective economics, objective science (and so on). To borrow a term from scientist and philosopher Karen Barad, such views exercise a ‘hegemony’ over our world which places us all in jeopardy.

Fourth Movement: The others in things and relations

It is, of course, not only I who arrange things in my world. There are countless others who do so, too.

At first sight, this might not seem to mean much for a metaphysics. It is, however, of great significance to how we interact with others from day to day, whether on a personal, social, or political level.

As I survey my world, not only do I see things arranged around me, but I must deal with other relation-tracing beings. I need to take into account the complex and subtle ways in which they, too, are involved in ordering my world.

On the one hand, we arrange the world in our own minds. On the other, others arrange their worlds in their minds. These others may be one, or two, or several, or may include the whole world.

It is important for us to understand this, not only as a fact of our existence, but in terms of how others communicate what they arrange in their minds. How are we to discern their dispositions, plans, intentions (and so on), not to speak of the sufferings, desires, and hopes which lie behind them?

While we say that nature is a book, which (ideally) may be read, not so with others. Much of the way in which they have arranged things in their minds needs to be inferred from what we call semiotic codes: gestures, postures, commodity codes, esthetic codes, and so on—as well as language itself.

A frown, a jig, a nod of the head—President Kennedy’s visit to Berlin, the bomb under Mururoa, appearances on the Palace balcony, and a host of interpretive devices all make further demands on our understanding of the world.

This has an important consequence. All the science of motivation and manipulation cannot replace human rapport, responsiveness, and reciprocation. The way that my neighbour, a visitor from Africa, or my local MP communicates with me, cannot be replicated or, up to a point, even analysed. The subtleties of personal interactions now move closer to center stage.

I certainly ought not to treat others as things. In the words of the philosopher Martin Buber, another self is not merely an “it”—“he is not a thing among things, and does not consist of things”—he is not a number, say, or an entity, an abstraction, a cog in the machine—but represents a “Thou.”

We cannot bypass, scientifically, the subtleties and complexities of personhood. There is no substitute for the art of being human. This we know through the simple categories of things and relations.

Fifth Movement: Vanishing things and relations

A fifth movement now dissolves the twin concepts of things and relations, which were so important at the start of this article. In the process, this enables us to solve some key philosophical problems.

Wherever we examine relations, there we find new things in their place—and wherever we find new things in their place, there we find new relations. When we seek to define things, and the relations which exist between them, we find an infinite regress.

‘With this heat,’ I say, ‘there will soon be thunder.’ But how do I explain that? In fact, I do not know. A friend says, ‘Heat rises. Clouds form. Charges separate. That makes lightning—and thunder.’ But with new things, I have new relations between them—and with new relations, there will be new things.

Like a fractal image, things and relations reach into infinity. The more closely we look at them, the more we see—and more and more. Their essence flees away. They do not exist in themselves.

To put it another way, If all things are related to all things, and all things influence all things, then to isolate one thing and to call it a thing cannot be quite right. In fact, in many cases, our isolation of things—to the exclusion of everything else—has been disastrous. Our frequent exclusion of the environment is the pre-eminent example.

This applies to causes, too—since causes are events, which is things that happen.

In any situation where we claim that A caused B, we define both A and B. By defining them, we exclude everything which is not-A and not-B. This is often useful, but again, forces on us a view of the world which cannot be correct.

It might seem at first to stretch the imagination, but it is a necessary conclusion: because things do not exist in themselves, cause and effect cannot be shown to exist. This applies to every cause and effect, whether upward, downward, backward, forward, metaphysical, physical, or mental.

Someone might object. Even if we have no A’s or B’s—no events which cause events, no things which cause things, no objects, entities, elements (and so on), we still have a reality which is bound by the laws of the universe. There is some kind of something which is not free.

Yet every scientific law is about A’s and B’s. Whatever is out there, it has nothing in common with such a scheme—at least, not that we can know.

This has major consequences. It relates to determinism, which can only be known to exist if things exist in themselves. It relates to history, which is only known to be objective where we can define its actors. It relates even to God, who is only definitely banished from this world where we can define mechanisms which replace God.

Endless inter-relatedness

No matter what the things and relations which we busy ourselves with from day to day, this too-brief article describes how we may—in fact, should—be continally aware of all relations in the global system which is the world.

There is more to this world than (among other things) self-interested preoccuptaions, or the hegemony of physics, economics, or history. In fact it has been suggested many times that something must lie beyond the realm of cold reason. How should we recover it, and set it on a rational footing?

It begins with a close reading of things and relations. These things and relations, and the way we understand them, hold the key, in principle, to every area of knowledge and experience. Even the dissolution of things and relations may be understood in these terms.

Thomas Scarborough is the author of Everything, Briefly: A Postmodern Philosophy.

Everything, Briefly: A Postmodern Philosophy

By Thomas O. Scarborough

Wipf & Stock, June 14, 2022

Paperback ISBN 9781666734935

Hardcover ISBN 9781666791464

eBook ISBN 9781666791471

Kindle ASIN B0B51WQ4GH